MAGAZINE No 96 WINTER 2003

Edlines

It's that time of year again, when we oldies start bringing up the past. That was the theme in our local paper, whose magazine section editor has a bit of a sense of humour. He was talking about reissuing old pop and rock numbers by the original artists, now wrinklies, and published the best of those sent in by readers.

General ageist:

We're all going on a Saga Holiday - Cliff Richard.

Can't get no Sanatogen - The Rolling Stones.

Paint it Beige - the Rolling Stones

He ain't Heavy, He's my Grandad - The Hollies

Saturday Night at the Legion - The Drifters

Rocking Chair all over the World - Status Quo

The Air That I wheeze - The Hollies

Body Function:

Don't Go Bypassing my Heart - Elton John & Kiki Dee

Heard it through the Ear Trumpet - Marvin Gaye

Sample in a Bottle - The Police

Hippy Hippy Break - Swinging Blue Jeans

Coldfingers - Shirley Bassey

Albatruss - Fleetwood Mac

Mental Function:

Wherever Did I Lay my Hat - Paul Young

5, 4, 3, 2, now where was I? - Manfred Mann

What has this to do with Rochdales? Not a lot, except that some of our cars have improved over the years, whereas the owners .... If you can think of any others, why not write in? No need to wrestle with those new-fangled techythings, quill and parchment will do. Don't forget that 2nd class post is now 1s/-.

Do consider the plea by The Chair and think whether you could perhaps do your bit for the Club.

The Rochdale Owners Club needs you!

Chair Chat.

Well the sailing season is at an end, the boat is laid up for the winter, so it's time to get on with winter projects like building Rochdales. One of the agenda items from the last AGM, which is being looked at by your committee, is the provision of GT body section mouldings. After further discussion the committee have decided not to progress with the production of a complete set of moulds for the GT at the present time. Due to the fact that we have not had a single request for doors or bonnets since the moulds were produced over four years ago, the following compromise has been proposed. That is for the club to look for a sound body shell and have it stored in a safe place, so that in the event of a member needing a body section to carry out a repair to his car the club will be able to respond. So if anyone knows the whereabouts of a good shell then let us know.

The number of members in the club who are renovating pre-Olympics is growing therefore we must ensure that body mouldings can be produced in the future as these cars become more sought after and the need inevitably grows.

Another AGM and committee item was that of the clubs annual Cheshire Kit Car Show. As you know Ron has been at the sharp end of organizing this for a number of years and he is due to resign.

If the Show, which keeps our club solvent, is to continue then we need one or two members to come forward to build a new team. Ron and I have been discussing this and come up with the following groupings of jobs that need to be covered. Most of these are administrative jobs that must be put in place at crucial dates prior to the event, otherwise things don't happen on the day (Ron is good at this sort of thing, as past shows have proved).

Most of these jobs can be carried out from a remote location with the overall coordinator steering the show via phone or eMail. The setting up and running the Show on the day will still be down to the willing band who faithfully turn up each year. So I hope I have persuaded one or two of you out there that maybe you could find time to put a bit back into your Club. I am confident you are out there. Please contact Ron or myself if you can help in some way.

Cheshire Kit Car Show Job Groupings.

1. Overall coordinator.

2. Trade Stand organizer.

3. Contact for Car Clubs.

4. Publicity officer.

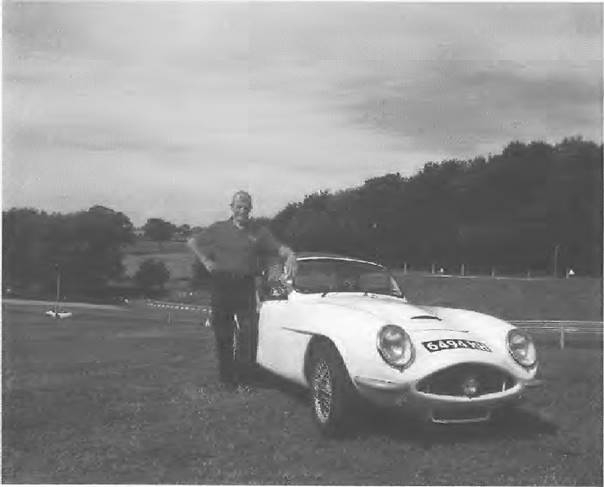

I should have mentioned in the last Mag. that my Riviera was going to be featured in a new magazine: Sports Car Classics. It came out in the November edition. It came about at this years Cheshire County Show, when a car correspondent asked if he could do a piece about the car for his Mag. The article was a bit over the top as far as my car is concerned, but I think it portrayed Rochdale Motor Panels in a good light. The day he came to do the photo shoot in July turned out to bright and sunny, so I took him down the road to Oulton Park were we were able to set the car up by the track while people were thrashing round on a track day.

So how many of you members out there have contacted our Sec. to get a list of members in your area? Christmas is coming! Wouldn't it be great if one or two groups could get set up by then? Why not arrange to meet at a member's house to see how the renovation is progressing and set a goal to have it finished for next years AGM. (I have a dream that at one AGM the turnout of pre-Olympics will be in the majority!! Well we can all dream).

While on the topic of pre-Olympics, my Mk.6 rebuild is making steady progress. As you may know the body shell of a Mk.6 starts life as a pure shell, like a jelly mould, with no internal bulkheads or wheel arches etc for stiffening. This is all left to builder to sort out. I suppose that is why so few of these cars were finished to anything like a standard, if at all.

The body on the car I am renovating was not fitted or finished at all well, hence the reason for making the new body out of the bits from three shells. It is still a bit like a patch work quilt, as the photo in the last Mag. showed, but I think it now starting to look more as it was intended. My aim is to have the body finished by the AGM (2004 ?).

Well I think that just about brings me up to date. So until next time.

Roger Coupe

The Mk 6 shell - it's amazing how much better a car looks with wheels in place.

****** LETTERS ******

From Neil Roshier in Australia.

I hope that this gets to you , what with the computer troubles you reported on....sometimes not worth trying to fix an old computer...except to get all the old information off it!

I was pleased to see the GT's being worked on in the new mag and I always admire Roger's work with the more obscure Rochdales. It would be good to see more of the GT's on the road. The thought struck me that perhaps this would be more likely if a 'new' chassis using more modern running gear (ie more modern than Ford pop etc...say MG Midget with a coil rear end?) was available through the club. A big ask I know, but Roger's work is so good and Duncan's old Alexis was quite memorable....what do you think, would we see more GT's restored/on the road if the performance was much better?

From Guy Stallard Rochdale GT 4 November 2003

It was nice to see you again at Burford and I apologise for not bringing the GT but the prospect of a three and half hour journey in the hot sultry weather was not very appealing. However I'm glad I brought my Berkeley 'restoration project' along, as it appears to have provided the inspiration to solve one of your problems. I hope you have a spare standard rack so you can swap them over to see the if theory and practice overlap or cancel each other out.

How refreshing to see the ROC 95 filled with articles on GTs instead of Olympics. I must admit that I have not used mine much this year now that my restored Lotus Elan S2 is now on the road. A big valve twin cam provides a little more excitement than 850ccs of Reliant power, especially in a summer like this one; there is also the added pleasure of an open roof.

Gordon Cowley's G.T. in Australia (ROC 95) could similarly be a 'bit short of go'. I didn't think that a 100E produces much more power than my Reliant engine and I don't like the look of all that steel box. Certainly in mine the performance is noticeably poorer with a passenger; perhaps they don't have hills in Oz!

Keep up the good work. Kind regards

***************************

From Richard Disbrow Phase 1 Olympic 15th October 2003

Finding myself a modest gap in between other old car activities I thought that I would try and improve the Olympic suspension. Firstly I tackled the wandering rear axle which was causing the tyres to rub on the inside of the wheel arches. When I pulled out the offside lower leading doughnut it was clear that there was a considerable gap between the short spigots, that protrude into the rear bulkhead, on the doughnuts. I reckoned that these short spigots were collapsing under cornering side loads. So I made up a short length of rubber tube about 5mm long, slid it over the lower offside trailing arm between the two doughnuts, thereby filling the void within the bulkhead hole. The rear end now seems a little 'wandery' and, as hoped, the rear tyres have stopped rubbing on the inside of the arches.

I have always thought that my Rochdale was pretty good in the dry, grip wise, but far too unpredictable in the wet, once resulting in a quick spin. Hands up, who has not spun his Rochdale? On a smooth dry race track, within the drivers modest limitations, it has proved to be as good as gold. I therefore reckoned that a bit of fine tuning would possibly improve things especially the wayward feeling when cornering in the wet.

So I knocked out the steering arms and dropped them into the lower holes in the upright which appeared to bring the steering rods more parallel to the wishbones. This was followed by new track rod ends, as the old ones were now not long enough, and a lazer tracking session. At the same time rear axle was then adjusted to line up with the front end. Surprise, surprise the handling was completely ruined with massive bump and roll steer and massive straight line instability. Back to the drawing board. The steering arms were returned to their previous location, taken back to the lazer tracking firm and the front tracking set up again. This time with a driver on board to give zero toe in. Apparently some lighter cars, ie the new Lotus Elite, need to be set up whilst loaded.

What a result! The car now seems more stable than it has ever felt before on both damp or dry roads, though I have yet to put it to the test in pouring rain. I think it goes to prove that before we start massively re-engineering these little plastic pigs it may well pay to sort out the basics first.

Questions; Who was driving the shiny red Olympic in Dorset between Blandford & Wimborne on 5th October? What are the stiffest torsion bars available to fit the Rochdale?

Regards

From Colin Ellis Ph II Olympic BJX 510 C 6 November 2003

July 2002 I succumbed to buying a Phase 11 Olympic. Martin Thomas moved in behind me a couple of years before and as I got to know him I found he had a selection of cars in bits including the Rochdale. As I had retired in April 02 it seemed a good excuse to keep me occupied in my retirement.

The body had suspension fitted and was on its wheels but had no steering and the rest was in boxes. Martin had done a lot of work and mods to the body including new petrol tanks and trailing arms, a three wiper mod and air vents behind the rear windows and also lots of other bits and pieces.

As it had not been on the road for about 25 years it needed engine and gearbox rebuild (Ford 1500) as well as making steering column etc.

With a lot of help from Martin and tolerance from Rochdale widow it is now on the road but still sorting out odds and sods. I took it to Burford on a trailer (before MOT) but could only stay for a couple of hours so did not get to meet many people; I enclose a photo which was taken at Burford.

We will be using it on classic tours alternating with our other classic which is a Sunbeam Imp Sport with a 1040cc engine, the Rochdale being the complete opposite. Hope to turn up at some Rochdale events in the future other commitments permitting.

Thanks for your note and photo. So your's was the Olympic that I missed at Burford! It's a pity, as there are several interesting techies on the car that I would have liked to see.

The wipers are the most obvious, though nearly obscured in the photo. I assume they use the BMC rack and pinion arrangement with an extra wheel box, which has the benefit of great simplicity. On my current Phase 2 I used a setup from the Citroen BX, which normally has a single wiper, and spent ages making the thing fit with a second arm. It works OK but the effort was hardly worth it. I was inspired to do this by 902 DUF, which was at Burford, and has a 2.9 litre V6 filling the engine bay (I'm not inspired to copy that). My next Phase 2 has the BMC rack with Allegro boxes. The sweep may be a bit small, but so long as they wipe and park OK I'm not fussed.

Alan Farrer 8 November 2003

Colins Phase 2 at Burford Photo - Colin Ellis

EDINBURGH HOME TO SOME OF THE WORLDS

FINEST SPORTS CARS THROUGH THE AGES.

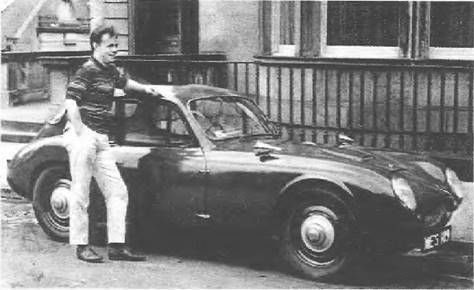

Thanks to Ron Collins for the above. Learmonth Terrace, Edinburgh. Top: 1959 Bottom: 2003

ROCHDALES FINEST

Back in the days when sports cars were scarce and scarcely affordable, it seemed like a good idea to build your own ideal vehicle and sell copies to like-minded enthusiasts. Mark Paxton reveals the secrets of Rochdale ....

King Cotton was dying. With each passing day his strength ebbed a little more, as one by one, his brick palaces fell silent. Cavernous cathedrals of production that had been filled with the deafening clatter of looms, slowly clogged with dust, blown into drifts by the chill breezes that slid through a hundred broken panes. But in one building in Rochdale, a new, quieter, rhythmic tapping heralded a different and brighter future, as two panel beaters, Harry Smith and Frank Butterworth, recently released from the restraints of uniform, worked away to build up their newly formed company, Rochdale Motor Panels.

Skilled men, they quickly turned their hand to making aluminium bodies for racing Austins, including several monocoque specials. As competition developed, lessons learned in aerodynamics during the war filtered through to the car world, and a less labour intensive method of construction, which was able to handle the new curves, was desperately needed. Their attention turned to glass fibre.

By the middle of 1952, four years after the companys formation, they launched the Rochdale Mk6. The new model was sold as a bodyshell that could be made to fit just about any chassis, as it left the customer to fabricate their own doors to fill the gap!

Special building took off in a big way in the 50's, as it allowed handy lads to create something that could compete with production sports cars, giving them a level of performance that otherwise would have been beyond their pockets. The market filled rapidly with dozens of manufacturers and bodies, but Rochdale were one of the first to grasp that the simpler they made it to build, the larger the number of sales would be. As a result, the ST (Sports Tourer) was born. Designed to sit on the freely available Ford Pop chassis and running gear, it was laid out for home assembly, with the minimum of tools required. The special had just evolved in to the fledgling kit car.

The GT followed in 1957, supplied as a rather more complete outfit, including glove compartments, hinged doors with locks, and even a grille. It was an instant success, with good reviews in the motoring press. Even using standard Ford bits, the weight saving alone was enough to gain 15mph on the top speed compared to its steel-bodied donor car. Bolt on some of the tuning parts that were available, and velocities in excess of the magic ton were possible. Very creditable indeed, making the cars a magnet for young men with an eye for speed and with light wallets.

Roger Coupe was just such a young man, and when he saw an advert for a new Paramount rolling chassis for £65, there was little doubt which manufacturer he would turn to for a body to clothe it. He chose the earlier Rochdale Mk6 for its flexibility, and set to. Once done, the car was sold on in order to buy a complete Paramount, itself a rare marque, made in Stoke on Trent. That was followed by a Peerless, before the needs of a growing family forced him towards something more mainstream.

Rochdale themselves were heading down the path that led to more sophistication as well. 1959 saw the arrival of the Riviera, basically a GT drophead, that within six months of its launch became available ready-bonded to a tubular chassis which made everything very rigid and strong. It also pointed the way to the next development, as 1960's Olympic was an all-glassfibre monocoque of immense strength. Although beaten into production by the Lotus Elite, the Rochdales body was of superior build and design, with the entire shell being laid up in one go. Holes were subsequently cut for the wheels and sump, with the exhaust recessed as well, giving a smooth under-belly, with an excellent drag co-efficient. The production process was quickly patented.

The mechanicals were either Morris 1000, Ford side-valve or Riley 1.5 with the body being supplied with appropriate mounts. The Ford option did not really take off, and the majority were sold ready for Moggy bits to be dropped in. By the end of 1961, the car could be bought with all new parts, in this form only needing fifty hours of the home enthusiasts time to finish.

With a top speed of 102mph, (120 with readily available tuning parts) and 0 to 60mph n 12 seconds, yet able to return 40mpg, once again the specialist press loved it. Motor commented that it stood comparison with the best from Italian and German manufacturers.

It is no surprise then, that when Roger was tempted back into the Rochdale fold in the early 1980's, that it was an Olympic he ended up with. After an 18 month restoration, he ran the car for the next decade, and became heavily involved with the owners club.

In October 1985, a brief item in a classic car mag caught his eye, where a Riviera had been found, dishevelled and abandoned, in a field. With less than fifty built, this was a very rare car, and he knew it must be saved. Despite the fact that the car had changed hands virtually as soon as he had heard about it, he rang the new owner, and offered help restoring it, if there was to be no chance of a sale. Contact was maintained over a long period of time with little hope of success, until out of the blue he was told it could be his, if he would pay £150. There was no hesitation.

Once the car had been trailered home, he cut the shell in half through the sills, and carefully lifted it off the chassis. Apart from a gaping hole in the off-side wheel arch, and another in the near-side sill, the glassfibre body had survived reasonably well. The large diameter tubular chassis, made by Halifax (who probably came by their name via the same original thinking as Rochdale!) was even better, and only needed cleaning and painting.

Satisfied that the Rochdale was definitely saveable, Roger was determined to complete the car with period fittings that would demonstrate just how good Rochdale could be. Starting with the body, the mouldings on the inner sills were cut back, which allowed the body to sit lower to the ground, giving a more sporting stance. The old bulkhead was cut out next, a mould made, a replacement laid up, and then bonded in place. Additional strengthening was added to the shell front and rear, then a petrol tank was knocked up from scratch and placed behind the seats, accessed by a Monza filler cap mounted on a panel above.

The Riviera came out of the factory without a boot of any description, which resulted in an enormous amount of dead space at the back. Undeterred, Roger marked out the shape of the proposed orifice, and cut away. The resulting hold was edged by a rebated water drain channel which also acted as support when the lid was down, and after making and bonding in a floor, hey presto, one boot!

The bonnet too was modified, with an elongated blister to cover a protruding carb, and then converted to open in the opposite direction from standard. While the mat and resin were still in his hand, Roger also made up some very tidy little quarter bumpers to add some low impact protection.

The doors, amazingly, came with wind-up windows, a rarity on kit cars, but their line was too high for Rogers liking, so he modified stainless steel Morris Traveller frames, cut down the quarter lights, and had some drop glass made. While he was at it, he added some Reliant Robin internal hinges for a smoother line.

With the doors done, his attention turned to a hood, which he again designed and built himself, having made paper template based on photos and drawings. These were transferred to canvas, to check the look and fit in 3D, with the result finally making it to a vinyl cloth. He was not finished there either, as a hood frame was knocked up that is both elegant and simple in its method of erection and attachment. A matching tonneau cover completed the ensemble.

Inside the car, he hand cut the dash from plywood, then veneered it in walnut before fitting a speedo, oil pressure and temp gauge combined, coolant gauge and a voltmeter, which covers just about everything you are likely to want to know.

A set of hand-made seats, re-trimmed in leather and piped, were matched by new door trims, and fitted carpet completed the interior. The body, with all the work done, was painted in Old English White.

The mechanical side was to receive similar levels of attention. The engine came via another Rochdale, this one found in the Isle of Man, which had a whole host of period extras attached. Once in Rogers hands, a standard Ford motor took the originals place, and the tuned one, once rebuilt, was dropped into the Rivieras engine bay. Based on the 100E, it has a Willment Power Master overhead inlet valve cylinder head fitted. A full-flow oil cooler and a eight pint sump keep things cool and well lubricated, aided by a Pilot V8 oil pump gear, modified to fit the original housing, which gives 30% better flow rates.

The head came complete with inlet manifolds, but Roger had to fabricate the exhaust one by hand, spending hours at a local garage, who patiently allowed him to measure bends, lengths and pipe diameters until he had a collection of bits. These, with final fettling and welding, did the job beautifully. With a pair of SU carbs and all the other mods, power has gone up from 30bhp to around 65.

The gearbox is Ford E93A, only a three-speeder, but with a set of close ratio cogs slipped into the cases, and with the change effected by a Wooler remote set-up that was found at an autojumble. At the rear, the live axle has a higher final drive ratio than standard, to make the most of the extra available power. A Fiat 500 steering box keeps the wheels pointing where asked, but as it is fitted ahead of the axle, a reverse linkage had to be made. A series of extra track rod mounts were drilled, to give options on ratios, should they ever by needed. Brakes are servo assisted, all hydraulic, and the car rides on a set of MGB wires, fitted to the Ford hubs with adapters that Roger turned out on a lathe.

Virtually all the parts used during the restoration were available around the time that people were building Rivieras, so it gives us an idea of the sort of performance that could be extracted by a home builder. So was it really a sports car?

Given the rarity of the beast, (it is believed to be the only road going car out of possibly five survivors), and the prospect of a reverse pattern, 3-speed non-synchro box, I was more than happy to let Roger drive, leaving me time to savour the experience.

And savour was the right word. The motor fired instantly with a vibrant, well rounded burble that promised thrills ahead. Once the temp gauge had risen high enough to lose the choke, the car was given its head along an empty stretch of road, and immediately impressed with its rate of acceleration. Clipping skilfully through the box with practised ease, the Riviera had enough get up and go to embarrass modern cars, and the power arrives in an even torquey stream.

Around the Cheshire lanes, the handling too deserved praise, with firm suspension happily co-existing with Fiats tight steering to give a package that could have been from a couple of decades later. It also underlined the amount of care taken when rebuilding the body, with it all feeling tight and together, without scuttle shake, or any untoward rattles or groans. Compared to the dreary saloons that most drivers were stuck with at the time, the Rochdale is a pure delight, and it is not hard to see why they were so highly regarded.

Why then, are they such a rare sight? Well, a catastrophic fire in 1961 destroyed all the moulds, and when production restarted, it was on a reduced scale, producing only the Olympic and a few repair panels for the Mk6. The company struggled to recover, but a patchy supply of parts combined with

falling sales, at a time when mainstream sports cars were becoming ever more affordable, proved too great a hill to climb. By the end of the 60s, production had dropped to about ten cars a year, and the Rochdale company moved into the more profitable world of heating engineering.

A sad end then to a noble enterprise and its products, once referred to as the 'British Porsche'. Having sampled the delights of Rogers car, it is clear that the Rochdale can stand shoulder to shoulder with any production car of its era, although I am not sure that they would all have been finished to such a high standard. In its current form, the Riviera has a level of fit, finish and performance that is a testament not only to Rogers commitment, but also to his superb engineering skills, and makes a mockery of terms like 'kit car'. Rochdales finest? Even Gracie Fields might have had to concede that one!

This article is reproduced with the kind permission of Sports Car Classic

The Riviera and its justifiably proud owner - photo. courtesy of Sports Car Classics

What are the small firms doing?

From Motor Sport June 1963

ROCHDALE

THE Rochdale Olympic shares, with the Lotus Elite, the distinction of being the only car to have a unit construction chassis moulded completely in glass-fibre and when we road- tested the prototype car in 1961 (June, 1961 issue) we were surprised to find an extremely stiff chassis/body unit with a good finish which handled well and gave impressive performance with the Riley 1.5 engine. Since then the Company has moved to new premises and has been turning out some five cars a week, which has kept the small firm pretty busy. However, development work has not stopped and although the basic formula is being retained a number of modifications have been incorporated into the Phase II model which was shown for the first time at the Racing Car Show.

Perhaps the most important change is in the use of the 1-litre five main bearing Ford Classic engine and all-synchromesh gearbox which brings the Rochdale into line with many other kit car builders who are abandoning the B.M.C. " A " and " B " series engines in favour of the rugged 105E and 116E units from Ford, whose Engine and Special Equipment Dept. is helpful to the smaller manufacturers who wish to use their products.

The Riley 1.5 or M.G. engine is still available but as the Ford unit is some 90 lb. lighter and is available with many tuning modifications this is the engine chosen by most buyers. The engine supplied with the kit is standard except for cylinder head modifications which bring the power output up to 75 b.h.p. Rochdale have recently received three of the Cortina G.T. engines which deliver 83.5 b.h.p. at 5,200 r.p.m. and are in the process of installing one in a car for test purposes.

Another modification on the Phase II model is the use of the Triumph Spitfire front suspension in place of the Riley torsion bar suspension. This layout utilises wishbones and coil springs with telescopic dampers and an anti-roll bar supplied by Rochdale. With this suspension come 9 in. dia. front disc brakes which are now standard equipment. Mounting points for the new suspension are bonded into the chassis.

The rear axle remains a B.M.C. unit, located by twin radius arms and a Panhard rod, suspended on coil springs with telescopic shock-absorbers. Experiments are being made with a simple swing axle type of rear suspension made by cutting the normal B.M.C. axle and mounting the differential unit on the chassis but Rochdale are loath to change a good rigid axle for an indifferent independent layout and there is no intention to change for the time being.

The remainder of the changes of the Phase II model are in the nature of improvements found desirable after three years of production with the Phase I. Perhaps the most important is a rear top-hinged door a la E-type which gives much easier access to the luggage space. By mounting the spare wheel underneath the floor of the car and fitting twin five-gallon petrol tanks more space has been found for luggage and in fact two small seats can be fitted in the rear compartment if desired.

Interior trimming has been greatly improved with a veneered fascia panel and a central console for switches, while the fascia edges are padded and covered with leathercloth. An interior light is now fitted and windscreen washers are standard. The bonnet of the Olympic is now slightly wider and the engine compartment layout has been improved for better accessibility. An electric cooling fan is also fitted in front of the radiator.

Homologation has just been applied for with the F.I.A., the engine being the 116E, which, of course, places it in a very hotly contested category but as several customers wish to race the Olympic, Rochdale directors F. Butterworth and H. Smith decided to have the car homologated. A good deal of interest has been shown from America in the Rochdale and arrangements are being made for exporting to the U.S.A. The bulk of sales, however, come from England where the car is available in kit form at £735 although it can be obtained for £930 completely assembled, and quite a number are to be seen on the roads.

The factory is laid out on two floors in its new premises (the first was destroyed by fire), the glass-fibre moulding being done on the ground floor and the mechanical work on the upper floor. The moulding of the Olympic is a patented process as it is the only glass-fibre car body which is moulded in one piece in the mould complete with the undershield. All minor glass-fibre parts like wheel arches and bulkheads are then bonded in while the shell is still in the mould. A steel tube passing over the windscreen is also bonded in during this process, for added safety in a roll-over accident. The Lotus Elite, the only other all glass-fibre car, is moulded in a number of separate pieces which are then bonded together.

The car is then passed to the trim shop where the car is fully upholstered and all electrical parts, lamps wiring loom, brake and petrol pipes are fitted and the rear axle is also fitted as this makes transportation for the owner an easier proposition. Assembly is then merely a matter of fitting the front suspension, engine and gearbox, wheels and various minor components. Rochdale claim that 50 man-hours will suffice to complete the car in every detail.

Rochdale have certainly proved that a monocoque car in glass fibre is a workable proposition and we shall be road-testing a car fitted with the 1,500 c.c. Cortina G.T. engine in a future issue. Details of the Olympic from Rochdale Motor Panels, Littledale Street, Rochdale, Lancs.

The body mould

Body/chassis units being finished

This view shows unusual hatch hinges door hinges?

|

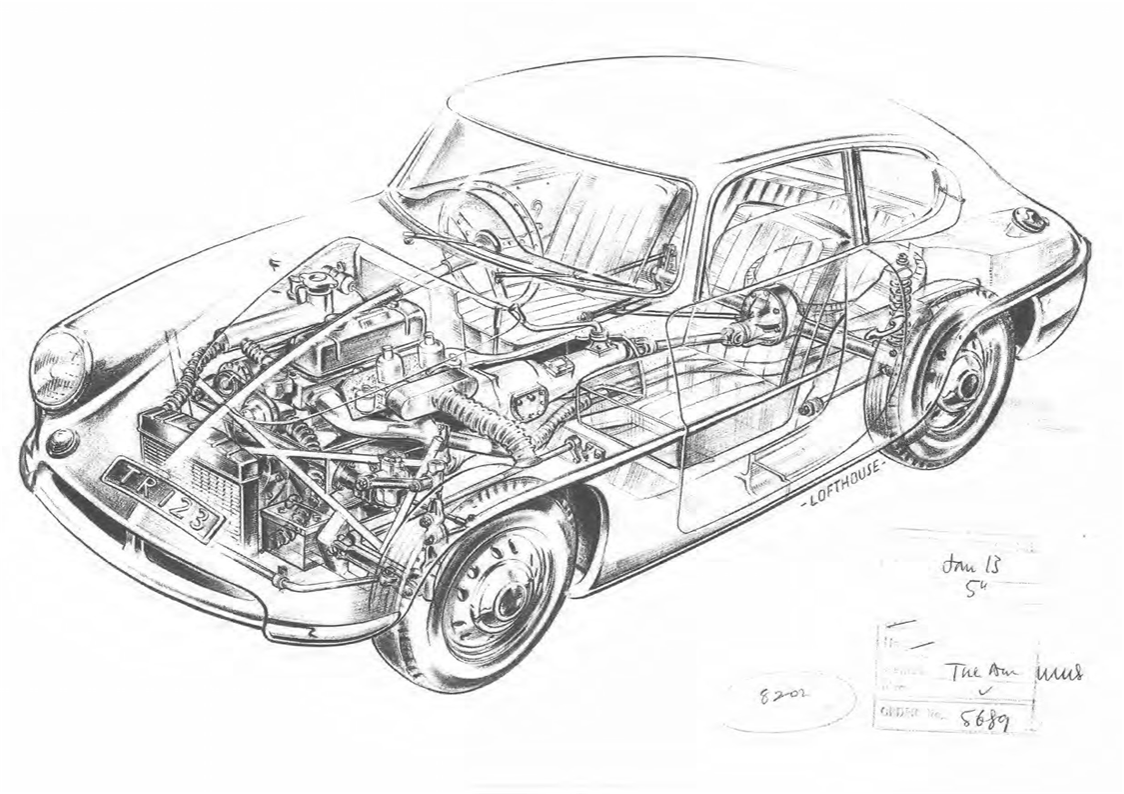

This super Lofthouse drawing of the Phase 1 Olympic will be familiar to most members. It was taken from the original Lofthouse Phase 1 Olympic artwork, ex Motor, now owned by Paul Narramore.

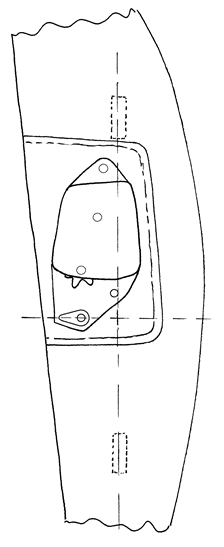

Fitting the Phase 2 Olympic Door Catch

(so that it works properly)

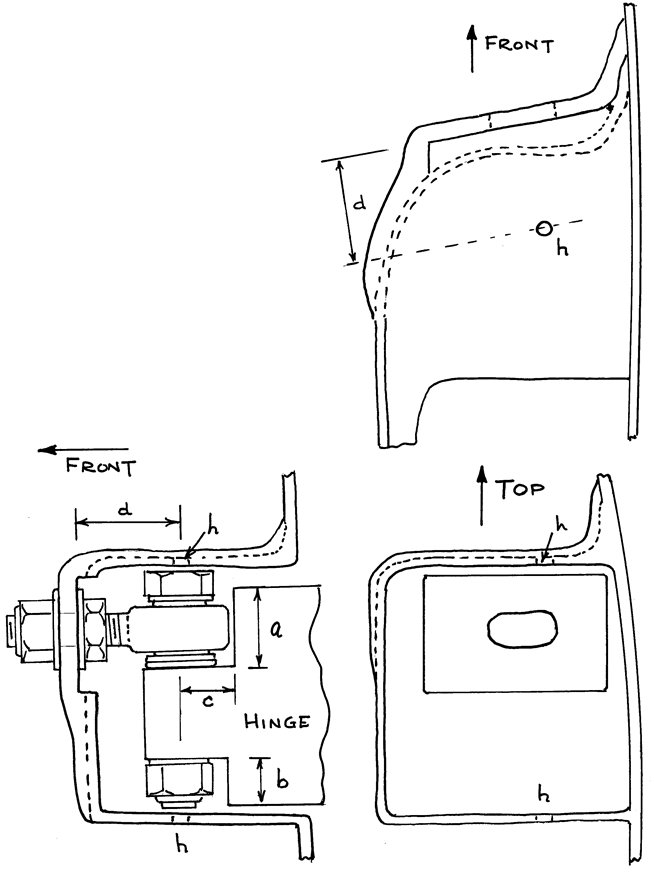

The catch fitted to both of my Phase 2's is the Willmott Breedon type fitted to many BMC cars of the 60's such as Morris 1100. It uses a rack and pinion system with the rack fitted to the striker plate on the jamb and the pinion fitted on the door catch. This also has a torpedo shaped guide which slides into a spring loaded slot on the striker plate. For the guide to slide smoothly into its slot it is necessary for the guide to be in line with its line of swing, ie at 90degrees to the axis of the door hinge pivots. If you can't visualise this, imagine that in the sketch here the torpedo is turned through 45degrees from the horizontal. As the door swung to, the torpedo would be at 45degrees to the slot and much too wide to enter.

Why do I mention this? Simply that when I was refurbishing the door on my 'new' Phase 2, I found that the door surfaces which supported the catches were nearly all hole, in traditional multi-owner Rochdale manner. I rebuilt the panels and had then to decide how to place the catch. Placing it in the orientation as shown here doesn't look quite right, in that the catch's centre line (although a bit vague), is not parallel to the recess in the door return. It is also quite different from where they had been originally, and which looked OK. Another factor is that the adjacent door panel is nowhere near vertical when fitted, which makes it difficult to align things. My 'old' Phase 2 also had the OK-looking orientation, but it has never closed smoothly. This confirmed my suspicions.

I trial fitted the catches on both doors and was relieved to find that it all worked perfectly. A technical difficulty lies in connecting the key-operated lock to the catch, as the Olympic door is much thicker than the 1100's, so there is a gap to be bridged, but nothing that a bit of bent metal won't fix.

Another minor problem

lay in the fact that on my car the doors are a tight fit in their openings, so

the catch tended to jam onto the striker plate. I solved this by rebating the

striker plate by about 3mm no big deal as the panel needed rebuilding anyway

(the fixing holes had nearly taken over and the panels were a bit flimsy too).

Another minor problem

lay in the fact that on my car the doors are a tight fit in their openings, so

the catch tended to jam onto the striker plate. I solved this by rebating the

striker plate by about 3mm no big deal as the panel needed rebuilding anyway

(the fixing holes had nearly taken over and the panels were a bit flimsy too).

![]() Another small point. Has anyone

else noticed that, with these door catches in combination with the normal

Olympic door handles (I'm not sure of their origin maybe Mini), unlocking the

door with the key doesn't unlock the door if it had been locked via the

internal lever? This occurs because the key locks (and unlocks) only the

pushbutton not the catch, which is locked by a separate mechanism.

Another small point. Has anyone

else noticed that, with these door catches in combination with the normal

Olympic door handles (I'm not sure of their origin maybe Mini), unlocking the

door with the key doesn't unlock the door if it had been locked via the

internal lever? This occurs because the key locks (and unlocks) only the

pushbutton not the catch, which is locked by a separate mechanism.

The

catch was designed for use with the Morris 1100 type handle, in which the key

turns a lever which locks the catch using the same mechanism as the internal

lever. The pushbutton is entirely separate from the lock. I have fitted such

handles to the Phase 2 and all operates as BMC intended.

The

catch was designed for use with the Morris 1100 type handle, in which the key

turns a lever which locks the catch using the same mechanism as the internal

lever. The pushbutton is entirely separate from the lock. I have fitted such

handles to the Phase 2 and all operates as BMC intended.

Alan Farrer

Olympic Hinge Whinge and Cure

The problems that beset the door hinges of the Olympic have generated a lot of interest over the years. To date five articles on ways to tackle the problem have appeared in the magazine. Here is a sixth.

Correctly assembled and lubricated the hinges should last for years, but the design of the hinge is not properly understood and many have been incorrectly assembled, possibly from new.

The alloy hinge should pivot on a pair of steel top hat bushes that should be clamped into the glassfibre hinge box by a vertical pin threaded on both ends, with a large diameter washer at each end of the pin under each nut to spread the load. For this to work the bushes must be longer than the hinge, but I have found many where they are shorter, with the result that the whole assembly becomes solid and pivots on the weakest part ie. the glassfibre.

Provision for lubrication is poor (pathetic), so the alloy hinges either wear, or the top hats rust onto the alloy hinges causing the bushes to (try to) turn on their shafts. As it is normal for the shafts to rust inside the top hat bushes too the whole assembly then turns in the glassfibre hinge box. The net result is a worn hinge box and doors that both drop and are stiff. It is then a major job to even dismantle the assembly, with further damage to both hinge assembly and box, as the pins have to be cut off to extract the hinges from their boxes. Rust is a serious problem here because the rain gutter channels water straight into the boxes and the hinges pivot in a pool of water.

A simple cure for poor lubrication is to fit grease nipples, but doing this without correcting the basic faults is a waste of energy. If the alloy parts are worn the usual cure is to drill or ream them out and fit oversize bushes (available from the Club).

A third problem is that the axes of the two hinges on each door are seldom aligned, so the hinge boxes are stressed as the door swings. The cure for this is to remove them from the doors and make the necessary adjustments to the mounting panels. If their fixing screws are rusted solid a common problem if my cars are anything to go by just removing them is a nightmare (though it should be done anyway, using stainless steel screws on renewal, to avoid future problems).

Another problem is the difficulty in fitting and adjusting the doors after refurbishment; if the holes in the box are not in the right place or, more likely, worn into an irregular shape, they have to be fettled and the hinge shifted across and bolted up anew. Matters are not improved by the inaccessibility of the top of the top hinge pin.

Finally, a quirk in the manufacture means that, on level ground, although the passenger door swings closed very gently (assuming it is in good order), that on the drivers side swings quite smartly, trapping the right foot. Am I the only person to experience this annoyance? The cause is that the axis of the hinge leans inwards more than that on the left side due to asymmetry in the body shape. It is not possible to correct this because the top of the top hinge pin would then clash with the body side.

The above sounds a rather sorry tale and so it is! Fortunately there is a cure for all these problems. Read on.

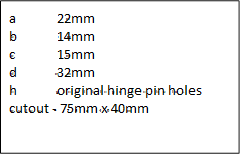

The general arrangement of the cure is shown in the sketches. The main thrust is that the hinge pin is replaced by a spherical joint.

Salient points are:

The size to use is an industry standard 7/16 UNF male right hand thread rod end, available from suppliers such as Demon Tweeks. A cheapo item (approx £10) is plenty good enough. Make sure you buy a lock nut, a Nylok nut and washers too.

Using spherical joints means there is no need to align the hinges on the doors (you should still replace the rusted screws with s/s).

A worn or damaged bore in the alloy is no problem as it is no longer a bearing surface. I used a 10mm s/s bolt to fix it to the joint. a sloppy fit although a 7/16 UNF item could be used by purists. In fact the alloy has to be in a dire state not to be re-usable eg. one of mine had burst due to internal corrosion.

The joint is well clear of any puddles in the box, so no corrosion. Filling in the existing top and bottom holes ensures the box stays watertight.

The single bolt fixing is much easier to fit than the pin arrangement and the nut is more accessible, especially for the top hinge. With a little practice one could remove and refit a door in under two minutes.

Adjustment is much easier: fore and aft is by adjustment of the thin lock nut and sideways by shifting in the slotted hole.

The only tricky adjustment is getting the vertical dimensions correct. The hole in each box should be arranged to be as high as possible without the head of the fixing bolt hitting the top of the box (measure the hinge/joint assembly to check). Note that the spacing between the joints must equal the distance between the mounting holes, since there is no free play available in the vertical. I measured the distance between the holes (using 'callipers' made from three pieces of wooden batten in a broad U shape) and made sure the joint separation was the same by adjusting the number of washers under one of the joints. Making one of the holes slightly oversize takes up any remaining error. The door height is then set by adding or subtracting the same number of washers under both joints.

Some constructional hints:

I cut the rectangular aperture in the top half of the back of the box (actually it's at the front relative to the car) using my trusty Dremel drill fitted with a small grindstone. To get the 32mm dimension I cut a plug made from Melamine coated chipboard to the size of this aperture and screwed a small stub of wood at 90degrees to it. After coating the plug with PVA release I then drilled a hole vertically through the stub 32mm from the front face of the plug and pushed a dowel through this and the original holes in the box with the plug poking through the aperture. The aperture was then glassed over to a thickness of about, wrapping the mat well round the box to ensure adequate strength (the box surface was cleaned and roughened beforehand). Pulling out the dowel and the plug resulted in a nice flat mounting surface for the rod end.

Note that this mounting surface is best angled in the top hinge, otherwise the fixing nut for the rod end bears against an angled surface as the glass mat curves onto the side wall of the car. It is as well to ensure that this surface is free from other bumps so that the fixing nut can bed properly.

Glassing over the bottom hinge is easy, but access to the top is difficult due to terrible accessibility. However it is no more difficult than repairing the top of the box when doing a conventional repair the top and bottom surfaces are often in a poor state due to damage caused when the hinge pin seizes due to corrosion or panic when hanging the door. I must admit it was easy for me as my Phase 2 was a very bare shell and had no dash assembly at the time!

Finally, glass over the old pin holes to ensure water-tightness.

So there you have it. This technique eliminates all of the problems inherent in the original design at a stroke. As a bonus, I was able to move the top bearing on the drivers side outboard sufficiently to make the door swing closed gently, as there was no pin to foul the bodywork, so my right foot will be safe! (Note that the hinge also had to be moved outboard by the same amount, but this was just part of the door refurbishment in my case).

Alan Farrer

|

|

Arrangement of the modified top hinge. Bottom hinge does not need angled plate in cutout.

Olympic Engine Variations

When the Olympic was first conceived it was intended to utilise Morris Minor components, which the company thought would be the new 'special builders' car, taking over from the Ford 10, upon which most of the previous model Rochdales had been based. This obviously included the Morris engine, which at that stage was only 948cc capacity. The car was therefore in direct competition with sports cars such as the mark 1 Austin Healey Sprite.

At some point between testing and production it was decided that, in order to give greater performance, a version utilising Riley 1.5 or Wolseley 1500 components would also be offered. Suspension wise this was relatively easy to achieve as the layout was very similar. The accommodation of the larger 'B' series engine and gearbox caused a few more compromises, making things less accessible. This of course meant the Olympic was now more of a competitor for the MGA and Triumph TRs. Both of these options were advertised as the 'A' type Olympic.

Presumably intending to appeal to their existing GT customers, who might want to retain the Ford 10 components with which they were familiar, an 'F' type Olympic was also offered using the Ford 1172cc sidevalve engine. This was never a popular option and very few were produced.

Initially the Olympic was offered as a monocoque body/chassis unit with certain special components only, rather than a complete kit and therefore the sourcing of standard components, including the engine, was left to the builder. Thus a variety of engines appeared in the early cars. Several versions of the 'B' series engine were then available from the Austin Cambridge/Morris Oxford to the more highly tuned MGA in either 1500cc or 1600cc versions, all of which were more or less a direct replacement for the Riley unit.

One 750 Motor Club member even managed to shoehorn one of the Twin Cam MGA engines into an Olympic. Although based on the 'B' series block the addition of a larger timing cover and the twin cam head made the unit physically much larger than the normal one and must have caused a few headaches. This particular car was advertised for sale in the late '60s and then disappeared. No doubt today the engine alone would be worth more than a complete Olympic.

Later, complete kits were offered, the two alternatives being either with Morris Minor or Riley 1.5 motive power at a cost of £625 and £670 respectively. As an option the Morris Minor engine could be substituted with a Ford 997cc 105E engine at no additional cost. The Ford 1340cc 109E engine was offered as an alternative to the Riley unit which reduced the price to £650. With the Riley kit a 1622cc MGA engine could be substituted for an additional cost of £25. The brochure also indicated that a Coventry Climax engine could also be provided, although I am not aware that any Olympics were actually supplied to this specification.

When the Phase 2 was introduced in 1963 the standard engine specification was for the Ford 1498cc 116E engine, fitted with a modified head, although the Riley 1.5 option was also retained. The cost for a complete kit had now risen to £735. Later the GT version of the Ford engine became more or less standard.

The Olympic, like other cars of the era supplied in kit form, has always been subject to modification by both the original and subsequent owners. A variety of engines have been installed in latter years to the surviving cars, usually in an attempt to provide more performance or make the vehicle more useable on a regular basis.

The later 1098cc and 1275cc 'A' series engines are a popular and easy swap for the earlier 948cc version. Similarly 1800cc MGB engines have found there way into a number of previously Riley engined cars. A number of Phase 2s have also received the later 1600cc crossflow engines, this being a relatively straightforward swap.

Other engines that have found there way under the bonnets of Olympics include the Fiat Twin Cam, Alfa Romeo, Ford Pinto, Toyota, Rover 'K' series and Triumph Herald. Most radical of course is the Ford Cosworth V6 used by Richard Parker, although this must be considered somewhat more than just an engine swap.

Is it any wonder that very few Olympics are identical under the bonnet?

Derek Bentley Olympic Registrar